JAMIE REID

BIOGRAPHY

“We made an impact on a lot of the population, particularly working class kids, and filled them with a spirit and belief in themselves.”

Jamie Reid

TAKING LIBERTIES!

Jamie Reid’s Political Work 1970-2021

British artist Jamie Reid (b.1947 d.2023) was an iconoclast, anarchist, punk, hippie, shit-stirring rebel and romantic. Infamously connected with the Sex Pistols and the DIY aesthetic of punk. Taking Liberties! featured drawings, stickers, posters, banners and publications from Reid's seminal but rarely seen early 1970s Suburban Press period through to 1980s and 1990s campaigns against the Poll Tax, English Heritage, the Criminal Justice Bill and Clause 28 to more recent work for Pussy Riot, Occupy London and Extinction Rebellion. Taking Liberties! addressed an important part of this influential artist’s work to date. At its heart, punk was both romantic and political, and Reid was the acknowledged driving force of rage against the monarchy, the state and the status quo. Reid grew up in suburban Croydon, under the parental influences of Druidry and social protest. As a boy, Jamie joined the Aldermaston march against nuclear weapons being stored on UK soil and was greatly impressed by an older brother who – having been involved with radical protest actions – would have been tried for treason had he been caught. Reid’s great uncle George Watson MacGregor Reid had been an early member of The Golden Dawn, a scholar of Eastern Mysticism who took on the mantle of Chief Druid in the early 1920’s. He was notoriously photographed being hauled away from Stonehenge by police after a Solstice protest.

By May 1968, Reid and his college pal Malcolm McLaren had become greatly impressed by events in Paris and by the actions and slogans of the Situationist Internationale. They tried to make it to the Left Bank in time for the rioting but found only the smouldering ruins and accompanying graffiti – ‘La barricade ferme la rue mais ouvre la voie.’, ‘Soyez réalistes, demandez l'impossible’ and best of all…’, ‘Vite! After a stint as a semi- professional footballer and gardener, Reid co-founded an independent, agit-prop press group called Suburban Press. Croydon was in the process of being carved up and ransacked by property developers and corrupt councillors, and through six issues and various collaborations with other radical groups, Reid honed his skills with scalpel, glue and Xerox machine to create punchy graphics that looked as good on bedroom walls as in the papers. Radical cyclists hammered Rolls Royces, goods were handed out free to kids in Selfridges, anarchy was building in the UK. Reid and McLaren knew exactly what they were doing with the Pistols. It was a smash and grab raid. It was intelligent, funny, violent and essentially Romantic. It couldn’t last.

Following the untimely death of punk, Reid decamped with his then partner Margi Clarke to Paris to escape the misery. Penniless, they convinced Polydor France to buy his songs, or rather the rapidly recalled lyrics to traditional Irish rebel ballads. Returning to Brixton in time for the riots of 1981, Reid started visual work again. This time on a mad, picaresque multimedia extravaganza called Leaving The 20th Century/How To Become Invisible, which after a single performance in Liverpool at the end of the decade, died a death. By this time, he was working with graphic designer Malcolm Garrett at Assorted iMaGes in the bleak streets of Shoreditch. He’d been given a space to work and a brand-new tool, a colour photocopier.

Jamie began copying, collaging, tearing and pasting, finding work for a disparate group of musicians including Boy George and Transvision Vamp. The end of the 80s saw Reid acknowledged as an important contemporary artist, as an integral part of Iwona Blaswick and Elizabeth Sussman’s influential survey of the Situationist Internationale, which travelled from the Centre George Pompidou Paris to the ICA in London and in Boston, USA. By this time, Reid had picked up the brush again. He’d been a keen painter of large-scale abstractions in college, moving the energy around and making marks. He now began explorations into sacred geometry and colour magic on rough canvas. It was at this point that another resident of the rambling Victorian warehouse commissioned Reid to refurbish his burgeoning recording studio. Ten years later, Reid and accomplice Mike Nicholls finished. The Strongroom Studios remained Reid’s largest project, with the entire complex of recording studios alive with his colours and glyphs. Throughout the 90’s Reid was engaged with protest movements – No Clause 28, Greenpeace, for the Anti-Poll Tax Alliance, against the Criminal Justice Bill, against English Heritage… By now he had relocated to Liverpool on a permanent basis. Always a loner who likes to collaborate, Reid had always moved away from a spotlight and found Liverpool to be more comfortable and more alive than elsewhere. He immersed himself in the local arts scene, notably with the radical arts group Visual Stress, with whom he collaborated on street actions, rituals and parades, principally directed at erasing the city's awful legacy from the slave trade. A major survey of his work to date occurred in NYC in 1997, subsequently travelling to Japan, Ireland and Greece.

Through early years of the 21st Century, Reid continued to paint and draw, often creating huge banners for Druidic rituals. Often riffing on familiar tropes of his self-created visual language and now working in partnership with printer Steve Lowe, Reid began to mine the possibilities of getting his work out through editions, enjoying the fast and cheap method of getting his work on walls, rather than fighting an art establishment desperate for young flesh. 2009’s collaboration with Japanese fashion icon Rei Kawakubo for her company Comme des Garcons brought Jamie’s work back to the catwalk, 30 years after his graphic work had made Vivienne Westwood’s Seditionaries line notorious. From 2010, Reid continued his involvement with important protest groups, like Occupy, Pussy Riot and Extinction Rebellion. The natural world also continued to be an ever present absorption, whether that be walking through Scotland and Wales, or sowing and harvesting on the allotment, it all fitted hand in hand, one informing the other. Always moving forward, always quick with a contrary opinion, and forever the free thinker, Reid became an integral part of a wonderful community enterprise in Toxteth, called the Florence Institute. Part art space, part community kitchen, part refugee resource and part refuge, the Florrie is a manifestation of Jamie’s dearest interests. Fashion continued to be fascinated by him. Most recently the Italian fashion company Valentino came to see him at The Florrie, taking away something unexpectedly kind and humane. It is in this human warmth and compassion where Jamie’s greatest strengths as an artist lie, and what he wants to do more than anything is to encourage others to fulfil their potential.

Jamie’s final, major project took place at the Lost Gardens of Heligan in Cornwall, who offered him a wildflower meadow and a blank slate. What emerged in 2022 was a 100m diameter OVA symbol (a conflation of an O for Compassion, a V for Victory and an A for Anarchy that he had used as his own glyph since the late 80’s), planted with corncockle and other wildflowers and orientated to true North. Along the eight adjoining points points on the outer circle, appropriate rituals were held throughout the course of the celestial calendar, beginning with May Day 2021, with - amongst others - local children and refugee groups invited to participate. For 2023, the outer wildflower planting was replaced with a heritage wheat (no GMO) that was later harvested for bread. Jamie was very pleased with this project, and was beamed in to the NUART festival in Aberdeen talk talk about it for his last public appearance before passing away peacefully at home on 8th August, 2023. His subsequent funeral began with a parade of friends from all periods of his life, bearing placards and banners. This was followed by wildflower seed sowing and a service with poetry and music, officiated by the Chief Druid. It was a great celebration of a creative life well-lived. As Jamie would always sign off, ‘All Love’. John Marchant, Brighton

Look to the future. Learn from the past. Live in the present.

A Conversation with Jamie Reid first published in The Idler 2008

Some years ago while living in New York I was asked to collaborate with the British artist Jamie Reid in organizing a large survey of his work to date called Peace Is Tough. It soon became apparent that the full extent of his work was a very broad canon indeed, from the endlessly reproduced and rehashed sustained volley of cultural musket-fire with the Sex Pistols to extremely contemplative nature-induced watercolours reflective of his deep connection with the earth’s subtler movements. Of course at first there seemed to be stark contradictions here but as I started to look at the work and get to know Jamie it started to coalesce. As the work arrived, so did his crew from his adopted home town of Liverpool. I lost count of them all but they all pulled together to produce a show called Peace Is Tough in a raw space in Manhattan that became, for the next six weeks, a locus for the inquisitive, a refuge, performance venue, doss house and dream space. In the intervening years, I’ve had the pleasure to get to know Jamie a little better. Spiritual descendent of post-Edwardian socialist reformer Chief Druid George Watson MacGregor Reid, Jamie takes ancestral sighting points as disparate as William Blake, Gerrard Winstanley and the Diggers, Thom Paine, Wat Tyler and Simon de Montfort: in the words of Julian Cope, all “righteous, forward-thinking muthafuckers”.There is however a smokescreen around him that veils his persona and work. He gets ignored by the art world for being unmalleable and gets pigeon-holed by an increasingly nostalgic press who only want to feed on the corpse of P*#k ad infinitum. It sees a good time to clear things a little.

A quick primer: Born in 1947, Jamie Reid was a founding member of Croydon–based Situationist-inspired graphics unit Suburban Press and was responsible for graphics and layout for Christopher Gray’s Leaving the 20th Century. In late 1975 Malcolm McLaren asked him to work with the Sex Pistols, providing both image and political agenda. Following their demise, Jamie drifted through places and projects – Bow Wow Wow, Paris, performance work, the Brixton squat scene. In 1987 ‘Up They Rise – the Incomplete Works of Jamie Reid’ was published by Faber and Faber – co-produced with music journalist Jon Savage it documented his influences and works to date. Following this breath for air, Reid got increasingly involved with various bands and protest movements - No Clause 28, the Legalise Cannabis Campaign, Reclaim the Streets and Warchild to name a few.In 1989 he started a ten year commission to revisualise and reinvent the interior spaces of both the recording and resting spaces of the East London-based Strongroom Studios using ‘colour magic and sacred geometry’ to encourage creativity and calm, As a result of this he also spent five years as visual coordinator with the band Afro-Celt Sound System. Since 1997 the retrospective “Peace Is Tough” has opened in New York, Tokyo, Dublin, Athens, Glasgow and Liverpool, including collage, painting, photography and film. He is currently finishing a heroically-proportioned 600-700 piece project based on the Druidic calendar – the Eightfold Year.*

We met again east of Knighton, Powys on the Welsh borders, at a spot fiercely contended in the wars with the English. It was also in this area in 1921 that the antiquarian photographer Alfred Watkins had a revelation on the hidden connections within the British landscape that he later wrote about in the indispensable Old Straight Track - and subsequently visited by the Lion of Judah himself – Emperor Haile Selassie!

“The root and inspiration and acknowledgement of the esoteric spirituality contained in the work comes from the ancient past and the distant future but is based in the immediate here and now.

It is indebted to those from the base root, the true guardians of the planet – the peasants.

Those of the earth

The rain and sun

The wind and stars

The seas the rivers

The valley the mountain tops

Mother Nature’s citizens those who tilled and toiled and understood the meaning of being.

Who loved the planet’s smallest intimacies and its universal magnitude and used it for the good of all. ”

The Mothers of Invention

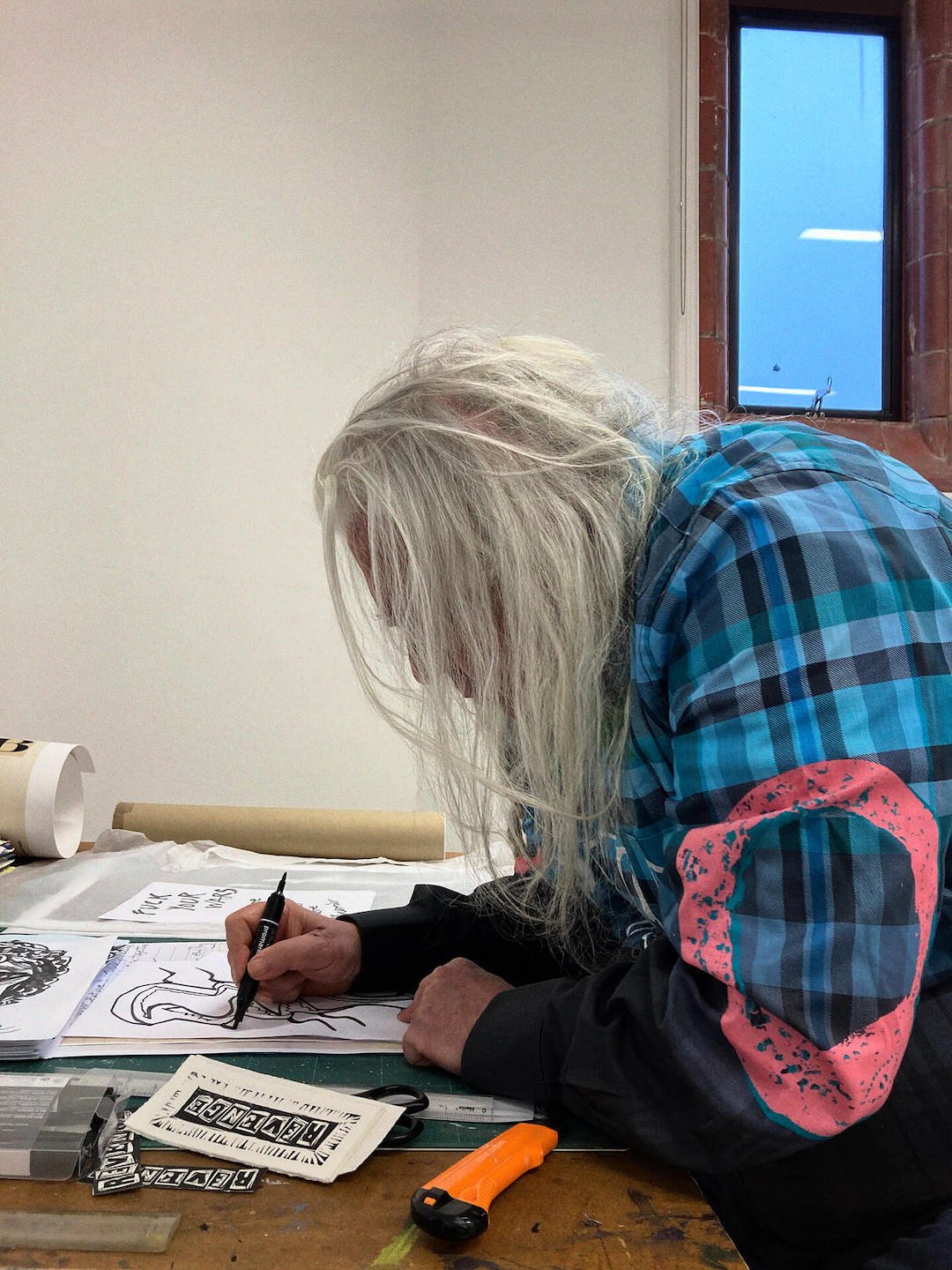

While we talk, Jamie takes out his trade tools and starts to paint.

John Marchant: Jamie, you spend a lot of time now with your hands in the soil. Can you tell me about that?

Jamie Reid: It is part and parcel... sowing, planting, growing, harvesting, nurturing. We are custodians of this planet.. the Garden of Eden, paradise on earth. We have mostly done our best to fuck the planet up. My work is deeply affected by my time spent working the land. Organic growth is integral to it. I’ll spend hours gardening and then go staight into hours of painting,they merge and intertwine with each other. It really is at the heart of my spiritual beliefs: love and respect for nature and our part within it.

JM: I think you still have to explain what you think a lot of your painting work is about, because people can’t get their head around it.

REID: I read an awful lot of Jung when I was 17 to19. That was the same time I was into R.D Laing and David Cooper and all that. Funnily enough that was all around that squatting scene.

JM: And what about about your belief system?

REID: Lapsed Druid! When you actually open things up to ordinary people – I mean ordinary people who would never fucking be bothered to go to an art gallery or museum – and I think quite rightly in lots of ways…I think magic has always existed to people of the land. They just knew – didn’t need loads of mumbo jumbo ritual, they just knew…because they fucking looked. And we can’t see anymore.

JM: Alfred Watkins says that the people who laid out the Old Straight Tracks attained a supernatural aura because they had a knowledge that other people didn’t. Isn’t it natural for people to want someone to look up to?

REID: As soon as you get pyramidical hierarchies the whole thing becomes corrupt. We’ve never lived in an age where people trust each other less. I can remember in Croydon, specifically in the early 1970’s when we were doing Suburban Press which was far from being elitist and was very involved with the working class in that area – that was the first time ever we didn’t have our doors open so it all started going then – but the whole Craig and Bentley thing really fucked Croydon. (Ed. the innocent and mentally ill Christopher Craig was hanged after his accomplice,the under-age Craig Bentley, killed PC Sidney Miles during a botched robbery in Croydon). Then the police wouldn’t go there. Croydon was very different then.

JM: Have you done any of your own research into ley-lines? What they are, what they mean?

REID: Only by observing and looking and seeing. A few years ago I was doing a lot of geometrical paintings. I tend to do them and then find the source. I knew about sacred geometry but it wasn’t until I immersed myself in it that I realised what it was. In a way there was always that element of being self-taught. It’s just such a fundamental element in everything – from primitive to the Renaissance to anything you care to name. You can see it reveal itself in front of your eyes in the landscape. You just immerse yourself in it – it’s just a total experience where you completely lose yourself. It’s the same as I feel when I’m actually working because I do go into a complete trance – which is why I can’t talk and paint. It’s very intense. It’s very deep in.

JM: Were you ever a teenager?

REID: I can’t remember! Maybe I’ve never stopped being one. I think music’s probably the biggest influence, from early rock‘n’roll. Croydon was a really big centre of early Teddy Boys …and the whole Bill Haley thing had a massive effect. But I suppose more than anything the biggest influence was what was happening in jazz in America at the time.

JM: Where was it coming from? Through the radio or through friends?

REID: I was buying it as it was coming out. That would have been predominantly Mingus, Coltrane, Pharoah Sanders, Archie Shepp, Ornette Coleman. To me it was like a whole peak of 20th Century culture. It’s never been surpassed. I also went to see a Pollock exhibition when I was about 16 without knowing anything about modern art and just found them like entering other worlds.

JM: You describe Pollock’s work as being like landscape painting.

REID: It was just like fantasy worlds you could walk into and see what you liked. I loved the fact that they left themselves open to interpretation. And Blake. I was obsessed with the Blakes in the Tate. A lot of that I got through my father. There was always art and sport, and I was lucky enough to be really good at sport. As you know I was going to play professional football or cricket. I also used to go up to see Mingus and Sonny Rollins perform at Ronnie Scott’s and Soho then was a big influence – at the same time Zappa, Beefheart and all that – it was an amazing period. There was a great element of experimentation. It was all part of a great belief in change, but I was brought up politically. My parents were diehard socialists and were very much involved – as was my brother – in the anti-war movement, so I was dragged off to Aldermasten marches at an early age.

JM: Your mother had problems with your Great Uncle George. She sounds like she was quite an iconoclast herself.

REID: She was brought up in a Naturist environment and her dad wrote a book called In The Heart of Democracy so they were all involved with the socialist movement of the time. It was the death of the whole fifty year epoch of Victorianism. There was a massive interest in change both politically and spiritually, which is the thing that fascinated me about the Druid order. There was a great belief in access to freedom of knowledge, education, the whole alternative movement in medicine and health, and health foods but they were as likely to be on trade union and suffragette rallies as be doing rituals at Stonehenge. It was all part and parcel, which is something I’ve really tried to continue myself.

JM: Do you think this was a direct response to the Second World War?

REID: Well the war drew a curtain on everything. It was the most massive blood sacrifice in the history of mankind. I’ll have to stop painting - I can’t paint and talk at the same time.

JM: Rolf Harris can do it. (ed. this was before The Great Revelation about the ghastly Rolf Harris)

REID: He’s better than me.

JM: 1968 was something of a watershed in the history of public protest – Paris burned in the belief that revolution was imminent, Martin Luther King was assassinated, the Tet Offensive began in Vietnam and medal winners Tommie Smith and John Carlos raised their fists for the Black Panther movement at the Mexico Olympics What was your experience of London in 1968?

REID: It was part of that whole R.D. Laing and Cooper period. Everyone was looking for alternatives. It was a period of fantastic possibilities and change. People really believed that you could actually change things, and politically, things couldn’t have become more repressed since then. We’ve become more and more under the thumb. We’ve lost our belief that people can effectively change anything. But on one level we’re going through a period of the most massive change that we’ve ever been through in the history of woman or man-kind. There is a quickening process – we’re experiencing everything that everyone’s ever been through over millennia in one generation. I think America is Rome and it will fall very fast. On an economic level it’s going to China and India isn’t it? I think everything might just break down. We’ll go back in to small states. China will beak up, India will break up, everywhere will break up into smaller units because people can only really survive in smaller units. I think they can only really appreciate what a wonderful planet…God, I sound like Louis Armstrong! It’s such a beautiful fucking place and we’re the custodians of it and fucking economics… is Babylon. People could be very happy with fuck all.

JM: Is this what connects the dots in your work – your wish to make people think that they can really enjoy this world?

REID: To a great degree, yeah. I suppose on one level there is that element in a majority of my stuff which tends to be around painting or photography or bits of filming that I’ve done. There’s an appreciation…a great element of beauty in it, just seeing the magnificence of things. And there’s obviously that other element – the political element – the punk collage, punk whatever you want to call it – agit-prop – which is making comment about the evilness of the powers that be. I don’t see any contradiction in the two but it’s something that I do suffer from as an artist, in terms of the people who run Culture. I don’t fit into one category. I would’ve thought that the whole idea of an artist is to be expansive, like an explorer going forward. Not stuck in a rut.

When it comes to a CV of exhibitions I’ve done about a third of them aren’t recorded. I did an exhibition with Ralph Rumney that I think Stewart Home organized. There was also a thing I did around the time of the first Gulf War which I did with John Michel in Camden – an exhibition about peace where he had all this sacred geometry stuff. If we’re talking about influences John Michel is one. The man is like a modern day wizard. I love him because he’s so benign. Such a lovely person.

JM: When did you first cross paths?

REID: Probably in the Sixties, with the pamphlets he did on sacred geometry and ley-lines. Obviously there’s the big connection from him to Watkins.

JM: So at last we get a mentor.

REID: A very gentle mentor.

JM: Where is he now?

REID: I think he still lives in Powis Square – I think he has done since the Sixties. In Notting Hill.

JM: You recently found out that MI5 had you down as a traitor.

REID: They were thinking of doing us for treason at the time of the Queen’s jubilee and God Save the Queen and all that.

JM: Is that encouraging?

REID: I dunno. I think it’s a family tradition. My brother was tried for treason when he was part of Spies For Peace and the Committee of One Hundred. See? Blame your parents!

JM: When you finish the Eightfold year cycle of work…what are you going to do next?

REID: I’d like to do more work like I did in the Strongroom. One of the things I’ve always wanted to do is to do a lot of landscape sculpture and create gardens. I spent five years doing landscape gardening when I was younger. I’d like to create places in which people can stay which act as resource centres. I’d like to apply what I’ve done in the Strongroom to all sorts of situations, it could be a hospital…obviously there’s a whole element to what I do that has that capacity to heal people.

JM: Colour magic?

REID: Yeah. I don’t think we know fuck all about colour and its potential. I don’t think we know fuck all about sound. I think we’re incredibly ignorant, however sophisticated we think our technology is. Actually, in a laborious way, technology hints at things we’ve lost the ability to see for ourselves. To me that was most well articulated by a Scottish engineer called Professor Alexander Thom who was a great expert on Stonehenge; he came to Stonehenge not through drugs or hippie-dom or New Age but through being an engineer and being fascinated with its structure. I remember him in a documentary – it was the time when Yale University had spent two years studying Stonehenge to say “Oh yes, it’s a cosmic time clock”. He was asked how on earth could these people could’ve built something like this without calculus. Fuck calculus. They were so in tune with the landscape, they were so in tune with the stars and their movements and the sun and the moon that they just knew. We had to spend thousand of years of calculus to come to these conclusions.

JM: I remember you saying that computers were going to bring in a whole age of…

REID: Backache and blindness.

JM: No, you said there would be a new age of psychic connection between people.

REID: I’ve probably got more cynical since I said that.

JM: The London Psychogeographical Association is about to post a section on their website about Druidry. What’s the connection?

REID: I think we touched on it earlier when we talked about the whole period of say, the Golden Dawn and the early Druid Order in Britain– it was as much politically bound as spiritually bound – it was part and parcel of the same thing. If you look at the early trade union movement it was as much spiritual as it was political – but those things have become less and less apparent.

JM: Beuys used ritual as the kick-off point for a lot of his work which is now relics of his rituals. What comes first for you? Do you use artwork in rituals or does the work come from ritual?

REID: They are totally intertwined and totally interdependent. The whole process of how I work is very ritualistic anyway, in many ways. Setting up, starting and just doing it – it’s very ritualistic – but I do go into a state of trance.

JM: Where do you go?

REID: You go into an absolute void – making your mind absolutely blank. Just letting it flow through.

JM: Do you have realizations in that state?

REID: Well, the realizations manifest themselves in what you do and what the product is. It’s as much science as it is art – it goes into all sorts of situations. It’s the high end of chemistry, physics, mathematics – things astrological. But you have to go through a deep sense of void and purity to do it. It’s macrocosms, it’s microcosms, but it’s fundamentally there to make people feel uplifted. To make people feel good. Well, that side of my work is, but there is the other side – the overtly political side that’s purely to make comment on how fucking evil the powers that be are.

JM: Lastly, in the light of all you have done: Ne Travaillez Jamais – please discuss!

REID: Well, our culture is geared towards enslavement, for people to perform pre-ordained functions, particularly in the workplace. I’ve always tried to encourage to think about that and do something about it.

*These are the eight festivals which divide the Wheel Of The Year. Each has it's own Druidic celebration, with occurrences approximately every six weeks. These include solstices, equinoxes, and the four major points in the turning of the Wheel, (Autumn, Winter, Spring, & Summer).

Recommended reading…

Up They Rise – The Incomplete Works of Jamie Reid by Jamie Reid and Jon Savage (Faber and Faber 1987).

The Old Straight Track by Alfred Watkins (Abacus 1974).

The Wing of Madness : The Life and Work of R.D. Laing by Daniel Burston (Harvard University Press 1998).

Jamie Reid: Artist and Visionary.

A slide presentation made to the Order of Bards, Ovates and Druids.

THE JAMIE REID ARCHIVE

-

Taking Liberties, Northampton Museum, NORTHAMPTON 2023

Taking Liberties, de Montfort University Gallery, LEICESTER 2023

Taking Liberties, University Gallery, BELFAST 2022.

Rogue Materials, Clerkenwell Gallery. LONDON 2021.

Taking Liberties, Barnsley Civic. ENGLAND 2021.

Taking Liberties, Made in Paisley. SCOTLAND 2021.

Taking Liberties, Horse Hospital. LONDON 2020.

Dragons Revenge, Galerie Simpson. SWANSEA 2019.

XXXXX, Humber Street Gallery. HULL 2018.

Short Sharp Shock, Rise Gallery. CROYDON 2016.

Casting Seeds, Florence Institute. LIVERPOOL 2016.

Ragged Kingdom, Biorama Projekt, Joachimsthal. GERMANY 2015.

Peace Is Tough, Galerie Simpson. SWANSEA 2015.

Ragged Kingdom, Galleria Civica di Modena. ITALY 2014.

Time For Magic, Regency Town House. BRIGHTON 2014.

Ragged Kingdom, Parco Gallery. TOKYO 2013.

Ragged Kingdom, Templeworks. LEEDS 2012.

Ragged Kingdom, Subliminal Projects. LOS ANGELES 2021.

Out Of The Dross, Liberty!, Paul Stolper Gallery. LONDON 2012.

Peace Is Tough, Bearpit. LONDON 2011.

Ragged Kingdom, London Newcastle Depot. LONDON 2011.

New Paintings, L-13 Gallery. LONDON 2010.

May Day, May Day, Aquarium Gallery. LONDON 2007.

Eightfold Year, Aquarium Gallery. LONDON 2006.

Slated, Aquarium Gallery. LONDON 2004.

New Works, Jump Ship Rat Gallery. LIVERPOOL 2002.

Peace Is Tough, Jump Ship Rat Gallery. LIVERPOOL 2001.

Peace Is Tough, Waterside Theatre. DERRY 2001.

Peace Is Tough, Arches. GLASGOW 2001.

Peace Is Tough, City Gallery. DUBLIN 1999.

Peace Is Tough, Bangor. WALES 1999.

Peace Is Tough, Workhaus. LIVERPOOL 1999.

Peace Is Tough, Gazi Arts Centre. ATHENS 1998.

Peace Is Tough, Artificial Gallery. NEW YORK 1997.

Celtic Surveyor, National Slate Museum. LLANBERIS 1994.

Shamanarchy, Evolution, Shoreditch. LONDON 1992.

Celtic Surveyor, Back To Basics. LEEDS 1992.

Celtic Surveyor. DRESDEN 1991.

Celtic Surveyor, Kunsthaus. BERLIN 1991.

Celtic Surveyor, Cornerhouse. MANCHESTER 1991.

Celtic Surveyor, 051 Media Centre. LIVERPOOL 1991.

Celtic Surveyor, Britannia Hall. DERRY 1991.

Strongroom I, Shoreditch. LONDON 1991.

Celtic Surveyor, Punk Yng Nghymru, Oriel Pendeitsh. CAERNARFON 1991.

Celtic Surveyor, Dixon Bate Gallery. MANCHESTER 1990.

Up They Rise, Parco Gallery, Nagoya. JAPAN 1989.

Up They Rise, Parco Studio, Osaka. JAPAN 1989.

Up They Rise, Parco Gallery, Shibuya. TOKYO 1989.

Strongroom II, Shoreditch. LONDON 1989.

Art Workshop. GLASGOW 1989.

Feature Gallery. CHICAGO 1987.

Josh Baer Gallery. NEW YORK 1986.

Hamilton's Gallery, Mayfair. LONDON 1986.

-

Now Form A Band, Binghampton University. USA 2021.

Lines of Flight, Ridley Road Project. LONDON 2021.

Art Strikes Back, Museum Jorn. DENMARK 2019.

Print! Tearing It Up, Somerset House. LONDON 2018.

Punk Weekend, Design Museum. LONDON 2017.

Punk In Britain, Galleria Carla Sozzani, Milan. ITALY 2016.

Nuart Festival, Stavanger. NORWAY 2015.

Art In The Streets, MoCA, Los Angeles. USA 2011.

Live! Art & Rock That Changed History, Centro Per l’Arte Contemporanea Pecci. ITALY 2011.

I Am A Cliché, CCBB, Rio. BRAZIL 2011.

I Am A Cliché, Recontres d’Arles. FRANCE 2010.

The S.I. And After.., the Aquarium. LONDON 2003.

Collage, Dundee Contemporary Arts. SCOTLAND 2002.

Golden Jubilee, Centre Of Attention. LONDON 2002.

Upfront and Personal: Three Decades of UK Political Graphics Korea Design Centre Seoul. KOREA 2002.

Sound Design. TAIWAN 2002.

Sound Design. NEW ZEALAND 2002.

Punk, V+A. LONDON 2001.

Art Tube 01, Piccadilly Line. LONDON 2001.

Punk, Apart Gallery. LONDON 2001.

Sound Design, British Council exhibition. UK 2000-02.

Sound Design Tour. ASIA 2000.

The Ideal Art Exhibition, 051 Media Centre, Liverpool. UK 1992.

Images Of Rock, Gotenborgs Konstmuseum, Gothenburg. SWEDEN 1991.

Images Of Rock, Leopold-Hoesch Museum, Duren. GERMANY 1991.

Images Of Rock, Kunsthallen Brandts Klaedfabrik, Odense. DENMARK 1990.

Thatcher, Young Unknowns. LONDON 1989.

On The Passage Of A Few People Through A Rather Brief Moment In Time, The Situationist International. ICA. BOSTON 1989.

Kettle's Yard Gallery, Cambridge. UK 1989.

John Heartfield Exhibition, Bluecoat Gallery, Liverpool. UK 1989.

Punk Shook Us Alive (And Dead), Melkweg. AMSTERDAM 1989.

On The Passage Of A Few People Through A Rather Brief Moment In Time, The Situationist International. ICA. LONDON 1989.

Sur Le Passage De Quelques Personnes á Travers Une Assez Courte Unite De Temps. Á propos de l'International Situationiste, Musée Nation d’Moderne,Centre Georges Pompidou. PARIS 1989.

Critical Montage, Chiswick. LONDON 1988.

International Graphics Fair, Earls Court. LONDON 1988.

Disc Cover, Arts Centre, Burnley. LONDON 1987.

Disc Cover, City Art Gallery, Edinburgh. SCOTLAND 1987.

Music Art Music, Camden Arts Centre. LONDON 1986

.

JAMIE REID

-

WEBSITE